Human beings are creatures of habit. Ours days have a particular rhythm to them, and behaviours we exhibit today are generally indicative of how we behaved yesterday and will behave tomorrow. Yet for how routine our lives can be, behavioural research conducted the last 50 years has found that people tend to struggle when asked to recall specific details about their day-to-day life.

For example, can you remember how many times yesterday you checked your email, or how many glasses of water you drank? Odds are high that you did in fact check your email and drink a few glasses of water, but to quantify these habits is easier said than done.

This inability for people to recall with precision the non-salient parts of their lives makes the use of tools like self-reporting surveys complicated. On the one hand, surveys are a fast, cheap, non-invasive way of reaching large segments of the population and collecting data. On the other hand, if the data gathered does not accurately represent reality, this can have negative consequences. The accuracy and potential ramifications of self-reported survey data is at the heart of the study iNudgeyou published in the leading behavioural science journal Behavioural Public Policy [1].

>> Open Access to the academic paper: Reporting on one’s behaviour: a survey experiment on the nonvalidity of self-reported COVID-19 hygiene-relevant routine behaviours.

The Context

As the COVID-19 pandemic made its rapid spread in early 2020, policy makers across the globe sought to determine how compliant citizens of their respective nations were to hygiene and safety measures recommended by public health authorities. Large scale surveys, like Aarhus University’s HOPE project [2], were employed and the gathered data were ultimately used to inform actions taken by the government. A prime example of this was the implementation of extended lockdowns in Denmark after data suggested a dip in the Dane’s handwashing compliance.

Given the importance placed on survey data in the COVID-19 setting, iNudgeyou set out to look at the credibility of such results by offering up a small-scale version of the HOPE project’s poll with a twist: rather than merely asking participants to recall and quantify COVID-19 relevant behaviors off the cuff, we provided anchoring points around which responses might be assessed.

The Study

Partnering with the Gallup marketing firm, we surveyed 1001 Danish adults from June 9 to June 12, 2020 with a focus on 2 behaviours: hand hygiene and social distancing. Survey respondents were asked the following questions designed to mimic closely the original HOPE project queries:

- How many times did you wash/sanitise your hands the prior day?

- How many times were you within 2 meters of another person for more than 2 minutes the prior day?

Prior to asking each of these questions, however, participants were instructed to identify if the frequency of their own behavior was over, under, or equal to a benchmark value, or “anchor” point. For the washing/sanitising question, we employed 2 different anchor points: plausible high and low frequencies set at 3 for the low anchor and 30 for the high. In a similar manner, high and low anchors were assigned for the social distancing question, in which 3 was our low anchor, and 15 was the high.

The Results

Given that the existing body of behavioural research suggests survey results are prone to error for numerous reasons, it perhaps comes as no surprise that our investigation confirmed anchors do impact how survey participants recall and report their own behaviours.

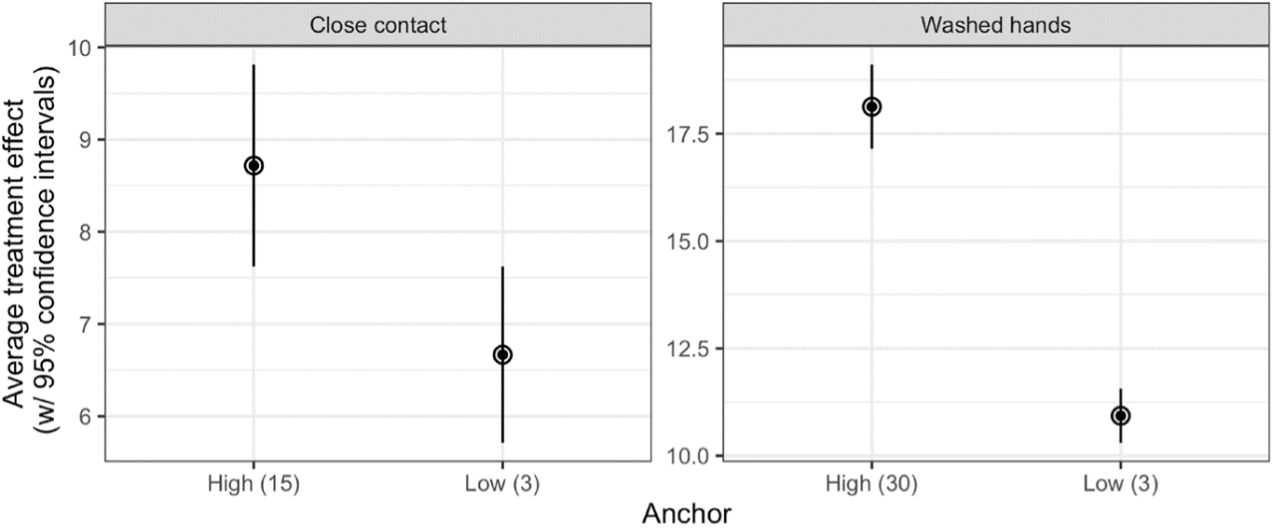

In the case of social distancing, those provided with the low anchor value reported an average of 6.7 close interactions the previous day while the high anchor group averaged 8.7 interactions, an increase of 2. Similarly, members of the low anchor hand hygiene group averaged 10.9 handwashes, while the high anchor group reported 18.1 average handwashes, a staggering increase of 7.2. (See graphs of averages mapped out below.)

In both the social distancing and hand hygiene scenarios, the degree of change between the low and high anchor averages was found to be statistically significant. It is particularly interesting how dramatic an effect anchoring had on hand washing compliance, however.

There is an apparent drop of nearly 50% in compliance when the low anchor was used! It is not clear why the effect of anchoring was so much greater in the handwashing setting but the data does provide strong evidence that handwashing recall is highly susceptible to outside influences.

The Takeaway

What then are the takeaways from our study? Certainly, we have seen that anchoring can affect the outcome of survey data, sometimes to a rather substantial degree. Beyond this, however, are the larger implications of acknowledging survey limitations:

- Whether participants have poor memory, feel societal pressure to inflate/deflate certain measures, or are prone to suggestibility, the end result is that surveys are (in most cases) simply not a reliable means of gathering accurate information on a populace’s routine behaviours.

- Rather than relying on self-reported data, particularly in settings where erroneous results may have an impact on many, routine behavioural patterns should be observed in their natural context.

With surveys of public health/routine behaviours becoming common during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is crucial that policy makers understand the limitations of this data before using it to enact changes that affect their citizens across the board. iNudgeyou is dedicated to pairing our accumulated knowledge of human behaviour with the generation of real-world data to help in situations just like this. We are always looking for new opportunities to partner with organisations for similar projects.

If you’re interested in working with us, we’d love to hear from you!

Get in contact

Together we can create a happier, healthier society, one nudge at a time.

If you liked this blogpost you would probably like this as well >> New Field Experiment: How to Nudge Hospital Visitors.

References

[1] Hansen, P., Larsen, E., & Gundersen, C. (2022). Reporting on one’s behavior: A survey experiment on the nonvalidity of self-reported COVID-19 hygiene-relevant routine behaviors. Behavioural Public Policy, 6(1), 34-51. doi: 10.1017/bpp.2021.13

[2] HOPE-project (2022). HOPE – How Democracies Cope with COVID-19 A Data-Driven Approach, available at https://hope-project.dk